Pestilence was not the only infectious disease to plague early modern Oxford. With its low-lying position, water meadows, and swamps, much of the city remained in an unsanitary state. Several colleges were built on graveyards, while some streets functioned as rubbish dumps. Steep rises in population led to overcrowding. Food and water were regularly contaminated. These conditions helped contagious diseases to thrive.

Such circumstances contributed to the outbreak of a ‘new disease’ in Oxford in 1643, most likely typhus. Termed ‘morbus campestris’ (camp fever), the disease appeared during the siege of Oxford by the Parliamentary army.

Measles, malaria, and numerous other diseases were endemic in Oxford in this period. Disease outside the city also prevented people attending university, such as James Burton (1745–1825), later a Magdalen fellow, who was unable to come to Oxford in 1758 due to a severe worm infection.

Magdalen also experienced repeat outbreaks of smallpox, which killed several of its fellows in the 17th century. Later, there were especially deadly outbreaks in Oxford in 1710, 1719, and 1728.

Research into epidemic disease continued throughout this period, with numerous printed books on the subject. Many physicians still advocated bloodletting as a treatment for smallpox. Henry Stubb noticed that when smallpox ‘raged’ in New College in 1660/1, few who had their blood let died, while all that died had not been phlebotomised.

Before Edward Jenner’s smallpox vaccine of 1796, infections could also be treated by variolation, introduced in the early 18th century. There was considerable official opposition at first from the city and the University to inoculation.

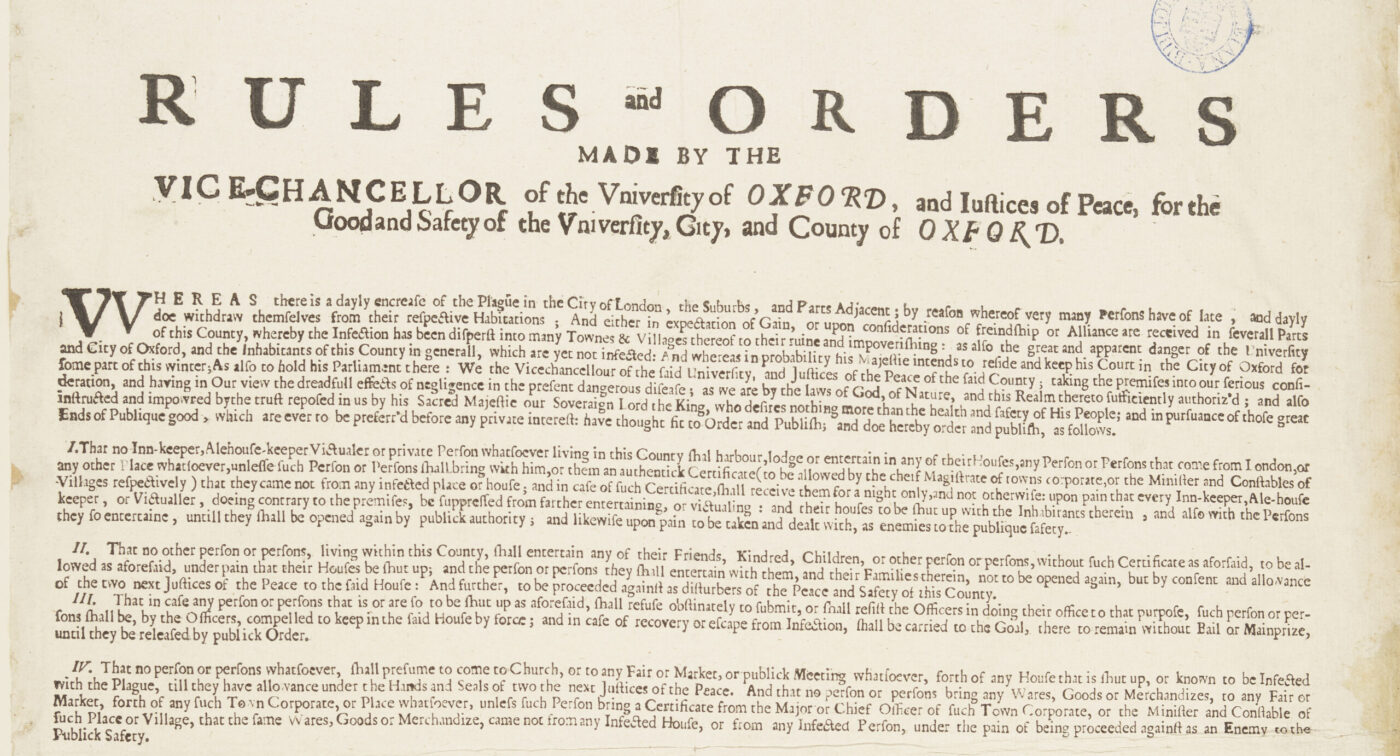

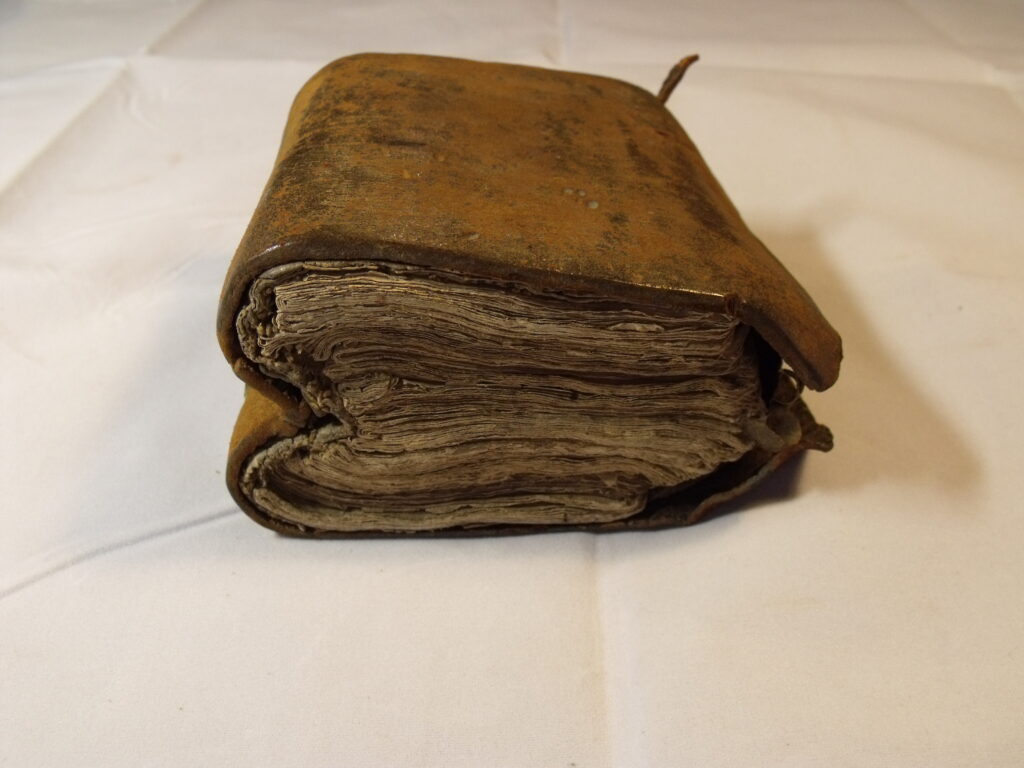

Medical Recipe Book

This small, portable manuscript is a compilation of medical recipes that appears to have passed between the hands of about half a dozen practitioners who all added to its contents. Produced in England in either the 15th or 16th century, it contains Latin and Middle English recipes, short tracts (mostly on urinalysis), and some astrology. It contains just one recipe for plague (since plague was deemed mostly untreatable) entitled Pulvus evacue pestilencie (powder evacuating pestilence).

Magdalen College Library, MS Lat. 221

Cures for Infectious Disease

This small manual describes the symptoms of and cures for fevers, smallpox, and measles. Written in English by James Cooke (1614–88), a surgeon in the Parliamentary army, the book was addressed to a popular audience rather than a learned one.

Cooke explained that smallpox and measles in particular were ‘contagious and killing many’. Bleeding was the best cure for these diseases and could also be used as a preventative measure against infection. When it came to influenza, however, Cooke believed that bleeding was harmful.

Magdalen College Library, r.6.5

Essay on Fevers

This important book on fevers helped its author—the English physician John Huxham (1692–1768)—to earn the Copley Medal from the Royal Society for contributions to medicine. A non-conformist, Huxham could not study at Oxford, so received his medical training in Leiden and Reims.

In this book, Huxham offers an influential categorisation of continuous fevers into either ‘inflammatory’ or ‘slow nervous’.

An admirer of Hippocrates and a promoter of the humoural theory of disease, Huxham advocated bloodletting for inflammatory fevers, and laxatives for slow nervous fevers.

Magdalen College Library, q.5.1

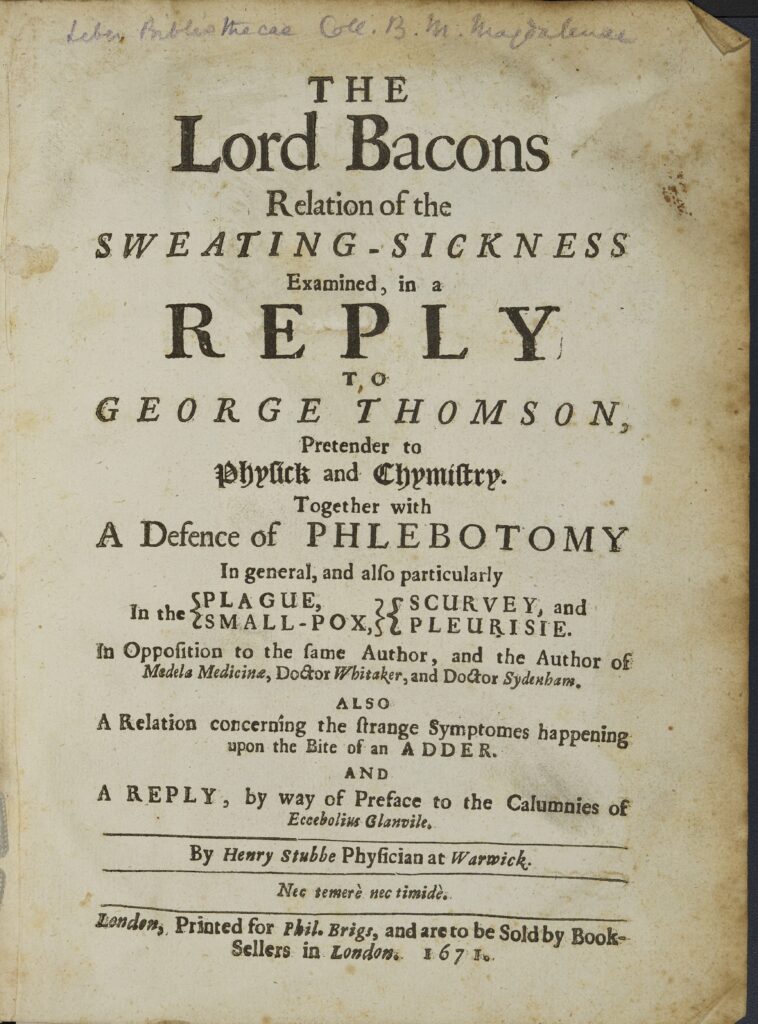

The Sweating-Sickness

This polemical pamphlet, written by the Oxford-educated physician Henry Stubbe (1632–76), was part of a broader defence of Oxford medical training, which had recently been attacked by members of the Royal Society.

Stubbe used a recent outbreak of the sweating-sickness as an example of how Royal Society virtuosos misdiagnosed and mistreated illness. Stubbe argued that bloodletting was ‘experimentally justified’ as a cure for pestilential disease.

Magdalen College Library, r.6.11

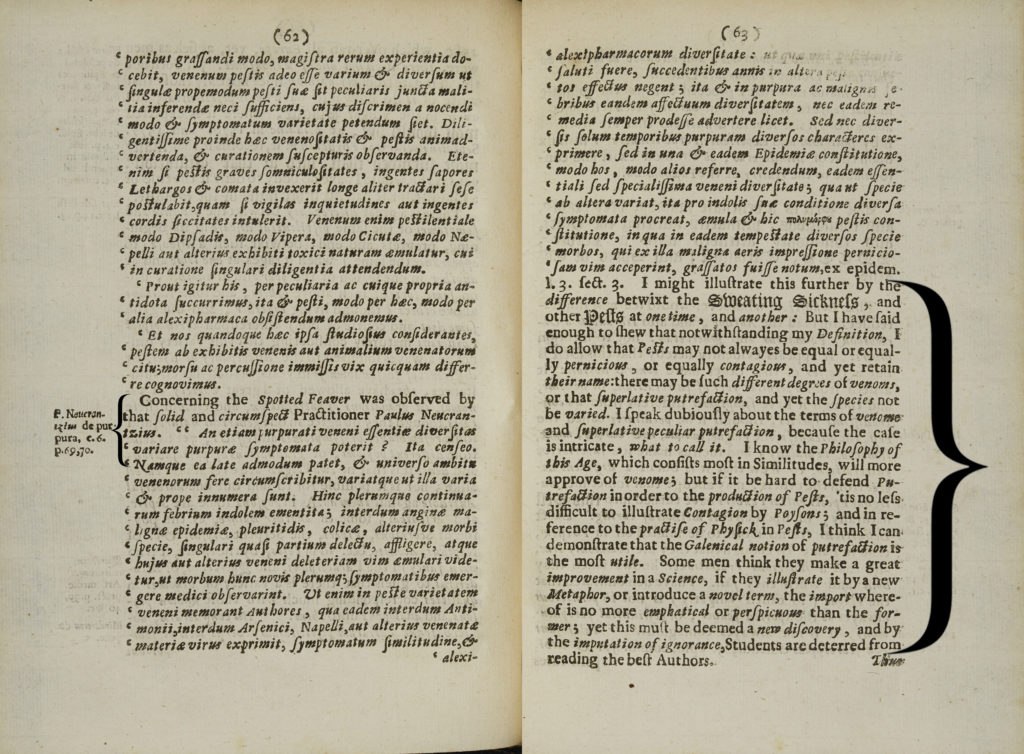

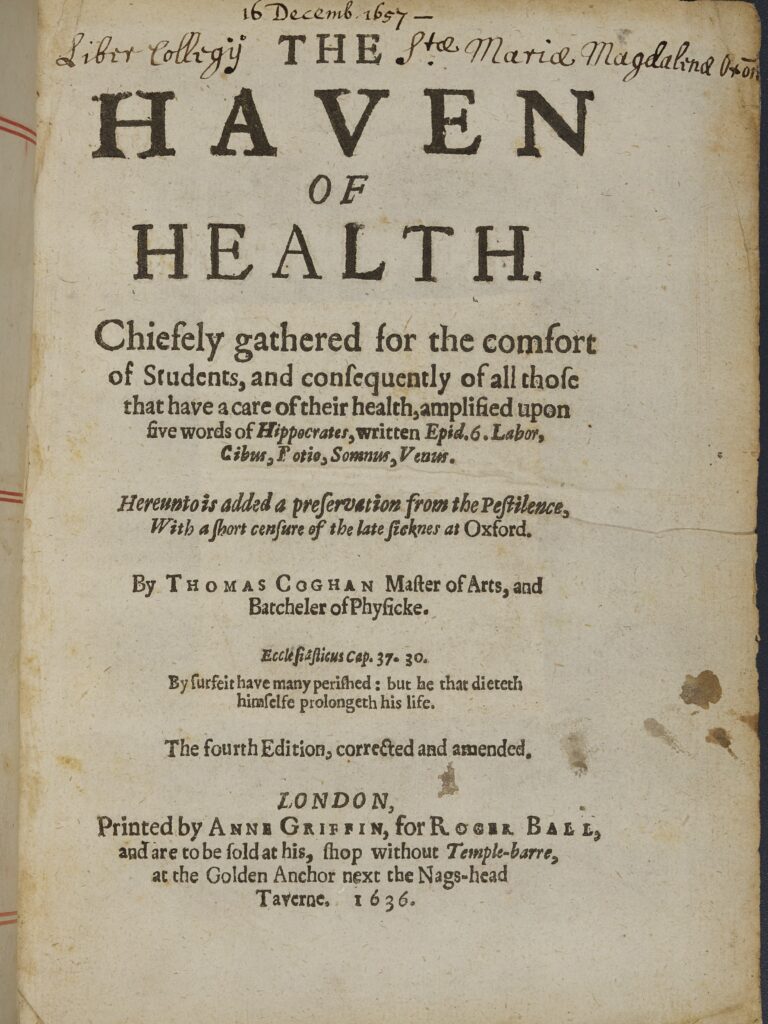

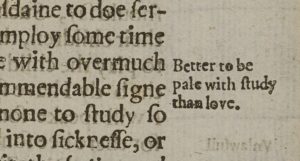

The Haven of Health

This book, first published in 1584, was written by the Oxford-trained physician Thomas Cogan (c.1545–1607) to improve the health literacy of students.

As well as advising them to avoid salt, venison, cheese, and strong wine, Cogan recommended clearing the mind by playing tennis and chess. He told students not to worry if they ‘waxe pale with overmuch study’, for it was ‘better to be pale with study than with love’!

As well as advising them to avoid salt, venison, cheese, and strong wine, Cogan recommended clearing the mind by playing tennis and chess. He told students not to worry if they ‘waxe pale with overmuch study’, for it was ‘better to be pale with study than with love’!

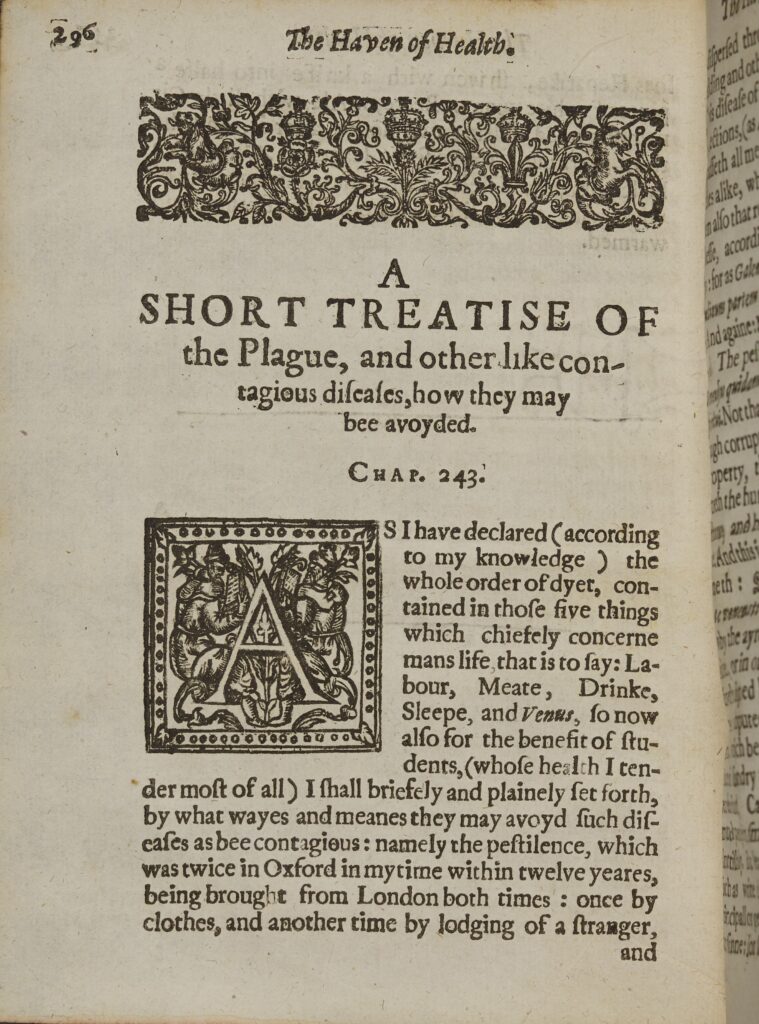

The book includes an essay on ‘preservation from the pestilence, with a short censure of the late sickness at Oxford’, which explained that the plague was sent ‘by the will of God as a scourge for sin’.

Magdalen College Library, R.6.18

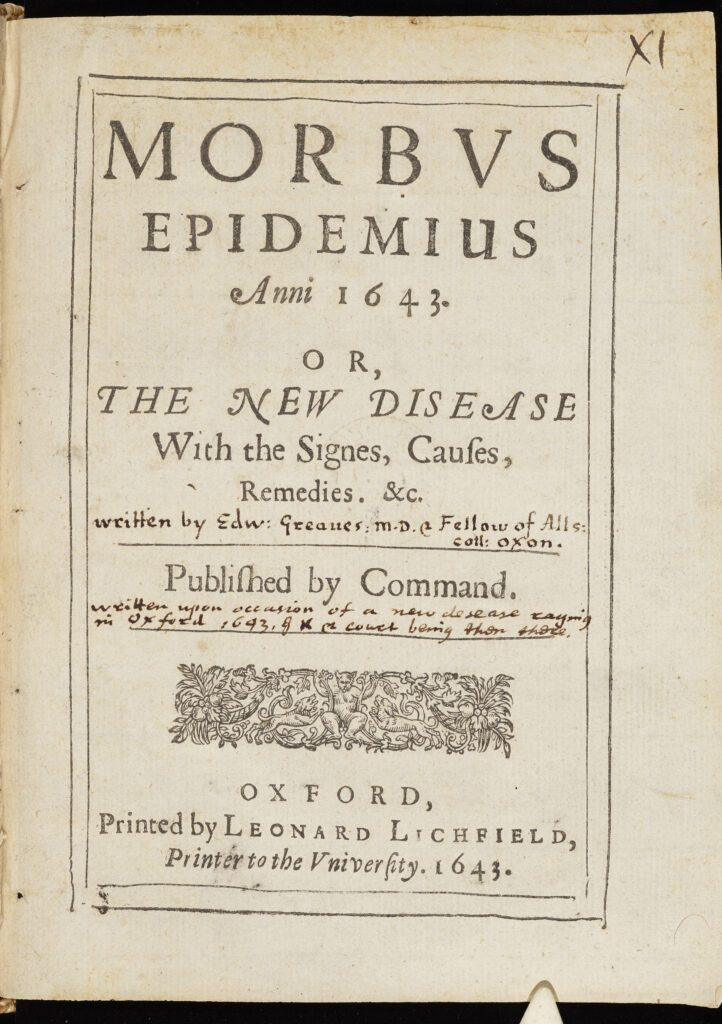

A New Disease in Oxford

This 1643 tract on the signs, causes, and remedies of an outbreak of typhus fever in Oxford was written by Edward Greaves (1608–80), a medical lecturer at Merton College. The disease was spreading quickly amongst soldiers who were housed in Oxford.

Greaves claimed the disease was sent by God as a punishment for sin, but God had used natural causes to bring it about. These included the air (it having been a hot and moist summer); the ‘influences of the starres’; contaminated water in the Isis River; and the ‘putrid exhalations’ coming from ‘Dung, Carcasses of dead Horses, and other Carrion’.

Greaves advocated sanitary reforms, namely ‘keeping the Streets sweet, and clean’, and ‘boyling’ water before drinking.

Bodleian Libraries, Oxford, Wood 498 (11)

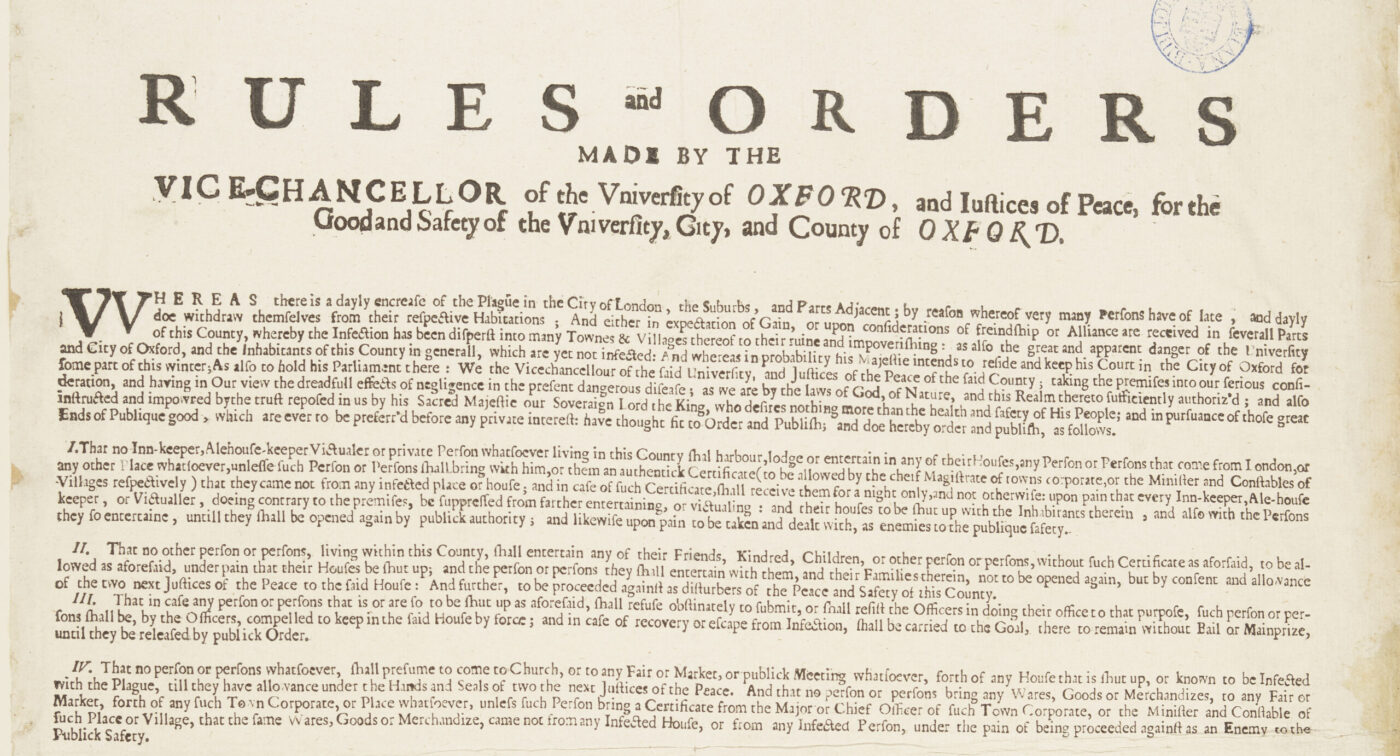

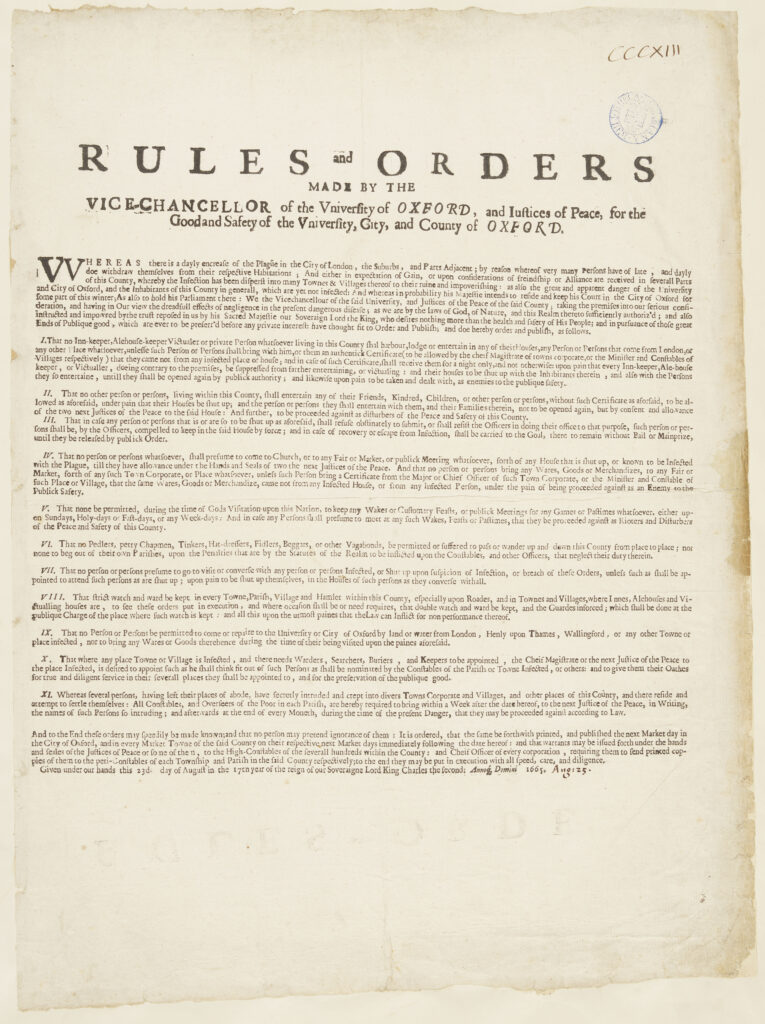

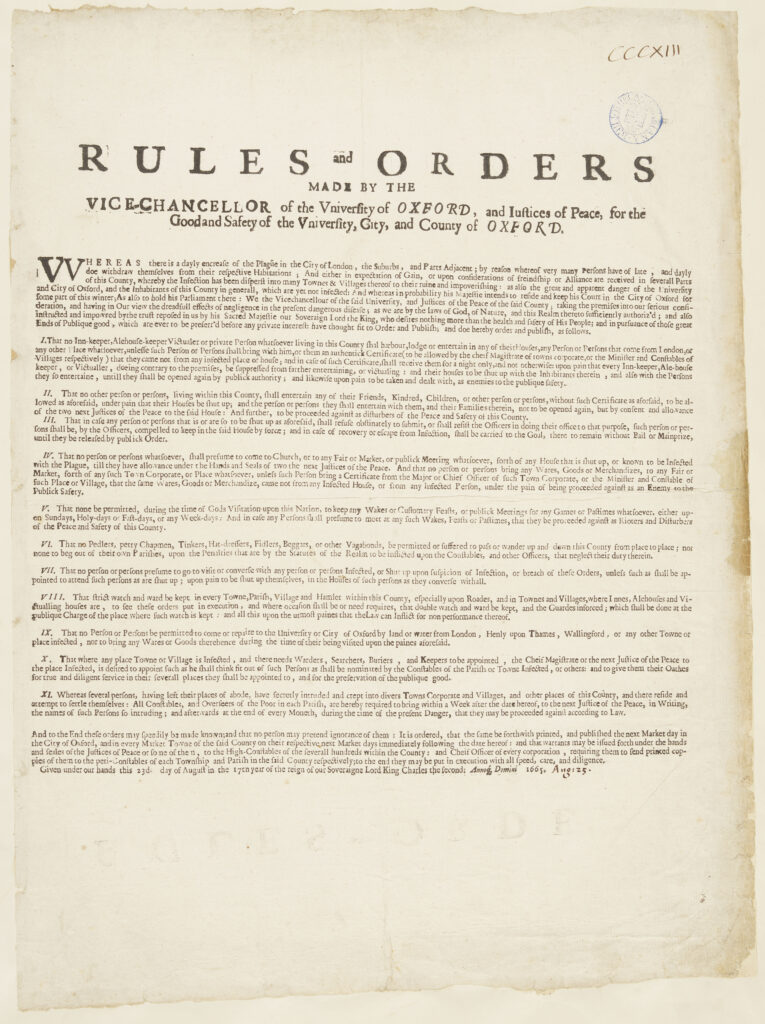

Vice-Chancellor’s Rules During Plague

This document was issued in August 1665 in response to the growing plague epidemic in London. Because the King and his court planned to reside in Oxford for some of the winter, it was feared the town might soon have an epidemic of its own.

The restrictions described here imitated strategies that had been in development in Europe since before the Black Death. The instructions were delivered for the ‘Publique good, which [is] ever to be preferr’d before any private interest’.

Bodleian Libraries, Oxford, Wood 276a, p. CCCXIII

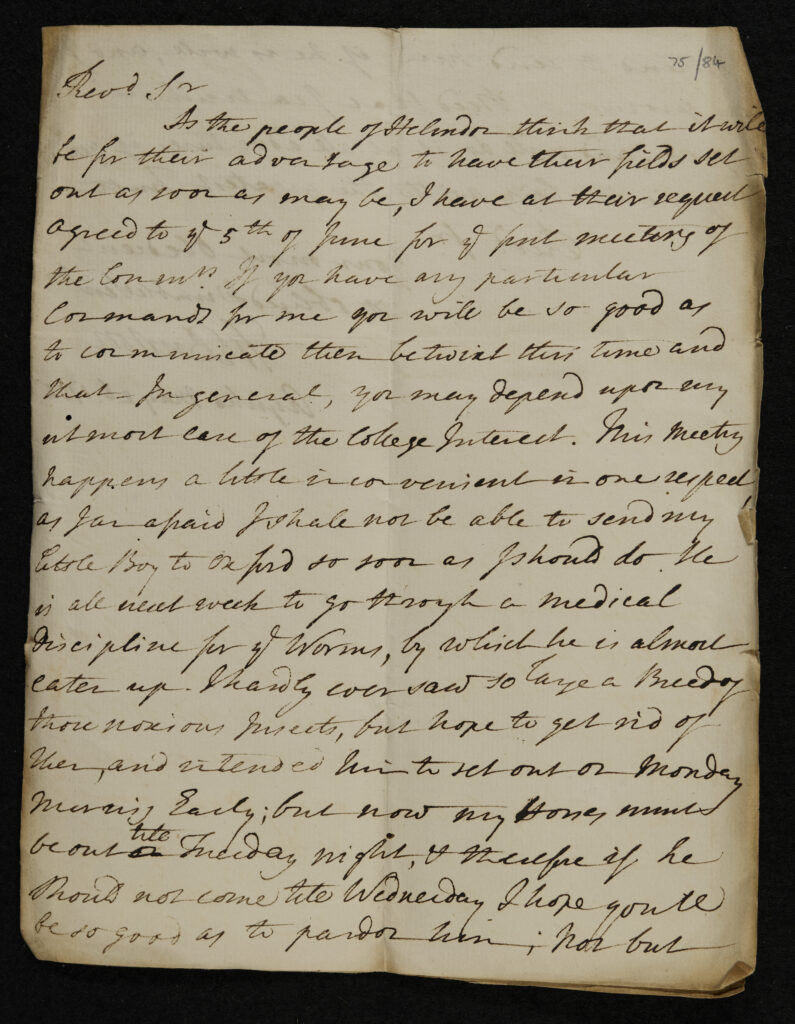

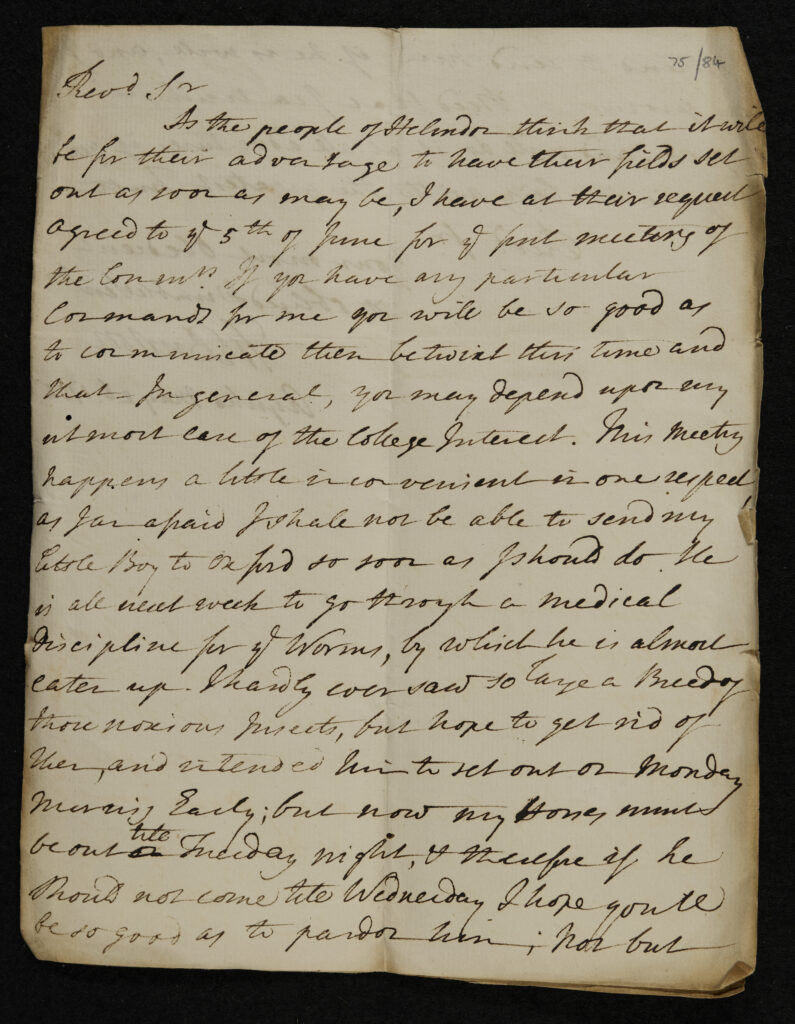

Worm Infection

Disease not only struck members while at Magdalen, it could also prevent them from coming to college at all. In this letter to Thomas Jenner (P 1745–68), Francis Burton reports how his son, James (pictured below), cannot come to Oxford on account of a serious worm infection.

Magdalen College Archives, EP75/84

Portrait

Pocket portrait of James Burton, Demy (1762–71) and Fellow (1771–75) of Magdalen.

Magdalen College Archives, E3/17